Tracing the Tide: Barbara Hammer on Elizabeth Bishop

In Barbara Hammer’s first film, Schizy, 1968, a split lens is used to present a double image from multiple points of view. Destabilizing vantage points are common occurrences in Hammer’s films. Wonderfully difficult to describe, Hammer’s films do share this common trait: onscreen and offscreen it’s Hammer’s own physicality that activates visual space.

Known for a respected practice of experimental works and refined essay films, Hammer’s camera-body movement is present in over 80 films: from a handheld motion to a hip swerve, such visual muscularity shows Hammer having “no anxieties about following [her] desire.” With her latest feature documentary, Welcome to this House, 2015, Hammer takes on the adventurous paths of another queer woman for whom precision, experimentation, and visual integrity match the complexity of Hammer’s own output. Elizabeth Bishop was reserved and shy, Hammer is dynamic and vivacious.

Welcome to this House introduces facets of Bishop’s life through some of the houses where Bishop lived, featuring three of her most loved homes filmed on location in Brazil and the USA. Tracing Bishop’s relationships through these homes—in Key West with Louise Crane, in Samambaia with Lota Macedo Soares, and finally on her own at Ouro Preto—is part of a larger investigation for Hammer. Making women’s intimate lives visible has been an ongoing focus for Hammer, and especially queer relationships where women’s intimacy has been historically erased, dismissed, minimized, or just completely sanitized. Bishop’s queerness was always an open secret, thoroughly steeped in poetic candor and uncompromising strides.

During the first minute of Welcome to this House an unruly wind scuttles through a seaside garden. It could have been filmed at Clear Comfort, Alice Austen’s home perched on the Hudson river’s edge, and site of Hammer’s The Female Closet in 1998. Despite this coincidence, it’s the house where Bishop grew up in Nova Scotia that opens the film. Bishop was raised by grandparents in Worcester, MA, the same city of the poet’s birth on February 8, 1911. Orphaned as an infant, Bishop moved in with her maternal grandparents in Nova Scotia, but moved back to Massachusetts when her father’s family obtained custody.

Bishop’s life is marked by vast quantities of private meanings and high-grade public achievements: Poet Laureate of the United States from 1949-50; the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1956; the National Book Award in 1970—nine years before passing away on October 6, 1979, in Boston where she lived in full view of the harbor.

Bishop saw herself “closely related to coastal areas,” as Barbara Page states in the film. In the poem One Art Bishop tells us that “the art of losing isn’t hard to master,” no matter how great a loss. The writer misses two cities, but their loss “wasn’t a disaster.” A proficient designer of momentum, Bishop points out in this poem from her last book, Geographies III, that worldly possessions matter very little. Was living in Brazil for 15 years an influence for perfecting the art of detachment? Was it the constant moving around? Or the need to make and remake a roaming studio on her own terms?

Hammer’s film doesn’t leave us with comfortable theories on Bishop, the film elucidates on the spaces where Bishop lived, loved, and worked: their textures and character as the sensory companions to an artist attentive to the way light lingered on and off surfaces. Bishop looked at everyday life by shifting attention to the unknowables gleaming on the underside of thought. For all her reserve, Bishop was never boring: her words are full of pep and pringle, tracing the tides that only someone well constituted to thinking across disciplines can do exceptionally.

Crucial to understanding how Bishop structured her words is this obvious refusal to be landlocked. Hammer’s film portrays this important element by not encasing Bishop’s work, her story, or even her open desires and private dismays. Hammer’s camera moves swiftly through these homes, reconciling the labor of extensive research with the vocabulary of Bishop’s imagination. Like Bishop, Hammer has perfected codes of movement suitable to her perceptions.

Bishop began studying at Vassar in 1930, seven years after another prominent Vassar graduate, Edna St. Vincent Millay, became the first woman to receive the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1923. As with many of her creative contemporaries with means, Bishop moved to Paris in the mid 30s with Louise Crane—Paris being the city where Millay was already situated, where Sylvia Beach had already launched a book store, where Natalie Barney was famously holding sapphic salons. In one of her poems about Paris, Bishop looks out from her Paris apartment and contemplates the homogeneity of the courtyard buildings, observing the looming interiority of such dwellings:

“It is like introspection/ To stare inside, or retrospection/ a star inside a rectangle, a recollection…”

Bishop’s simultaneous attention to surface and interiority was not lost on Hammer. Welcome to this House looks at Bishop’s houses from the outside and through the spatial dimensions that were Bishop’s foundation. One of the film’s greatest visual pleasures is in the buoyancy of Bishop’s words, suspended over Hammer’s visual streams. In one mesmerizing sequence, Bishop’s poetry is paired with layering waves and electric wires against a tropical blue twilight, an erotic counterpart to Bishop’s rhythms.

The story of Bishop is also a story of how women choose to give each other power. When the urban developer Lota de Macedo Soares builds Bishop a live-in studio adjacent to their home, it’s not a simple case of Macedo Soares giving her lover the symbolic room of her own. It’s also an act of making another world possible, one where Bishop will form, reform and reframe her work. Bishop and Macedo Soares were both workaholics. I imagine there was very little explanation required to convey the importance of work to each other.

Hammer’s film resituates domestic space as a place where women who blur gender roles exercise their will and power without being confined by traditional conventions of what a home should represent: throughout her homes Bishop prioritized pleasure and professional production over the standard narratives of domestic and gendered labor.

What follows is Patricia Silva's interview with Barbara Hammer, conducted over several months throughout 2015.

Patricia Silva: For Bishop—as with Stein, Dickinson, even Austen, and especially Woolf—home was where one was safe to be a queer woman. The subject of the studio often gets devalued as merely “domestic.” What your film does remarkably well is show Bishop’s many homes and studios, showing that the room of one’s own is quite portable for women who write, and a flexible space of security.

Barbara Hammer: You have an excellent point here, the home wasn’t always the ‘closet’ but in fact could provide safe haven for a different lifestyle not accepted by the general culture. Many visual artists as well as word artists, use a room in their home for their studio. They can arrange, plan, shift and dirty or tidy this non-domestic space as they wish. I say nondomestic because the writing or drawing area is off limits to dish washing, laundry, as well as the other myriad household rhythms. When one enters the ‘studio’ (even if it just part of a room), it is a unique, special place where the creator opens to enormous possibilities of innovation, as well as craft, perseverance, care and completion.

A project born in this free space can have a chance to help change the world. I think even what appears as the tiniest creative practice has great potential. Think of each of us lucky and privileged enough to have a home in the first place, going to our ‘special nook’, our extra bedroom, the converted garage and practicing freedom of expression through extreme risk taking. I’m not talking about ski jumping, but perhaps a small step across a divide to a place not seen/experienced/smelled before. I’m talking about creativity within one’s own space and time.

Patricia: Aside from the ability to work and proximity to water, where there any other constant elements among Bishop’s residences?

Barbara: From my research through visits to Bishop’s homes, I can say she preferred simplicity, understatement (as in her poetry), and separation (distance from community). The Key West house is not in the middle of town but several miles away, it is rustic and not elaborate. She was choosing similarities and familiarities of her childhood wood frame home in Great Village set on the edge of town. During Bishop’s time as well as now, Great Village consists of only 500 residents.

Of course, we have to think about the wealthy structure of Samambaia that Lota Mercedes de Sota was in the process of building when they fell in love. We know that Lota built a writing studio for Bishop that was stuck away at the edge of the property, isolated, very, very simple and unadorned. We don’t know whose idea this was but my bet was Elizabeth said (this is total conjecture) “I can’t write in this glass house. I need my own space away and private.”

Louis Wharf, Bishop’s last home, an apartment in a new complex (yes, right on the water), was, still, in my opinion simple. Red brick walls, rough exterior overhead beams, wood floors and very isolated from the greater Boston area. Friends had difficulty reaching her and feared it was inconvenient for an older woman to be so far from the conveniences of grocery stores, etc. Bishop chose to be there and bought the apartment in an abandoned wharf even before construction had begun. She knew what she wanted and she made sure she got it.

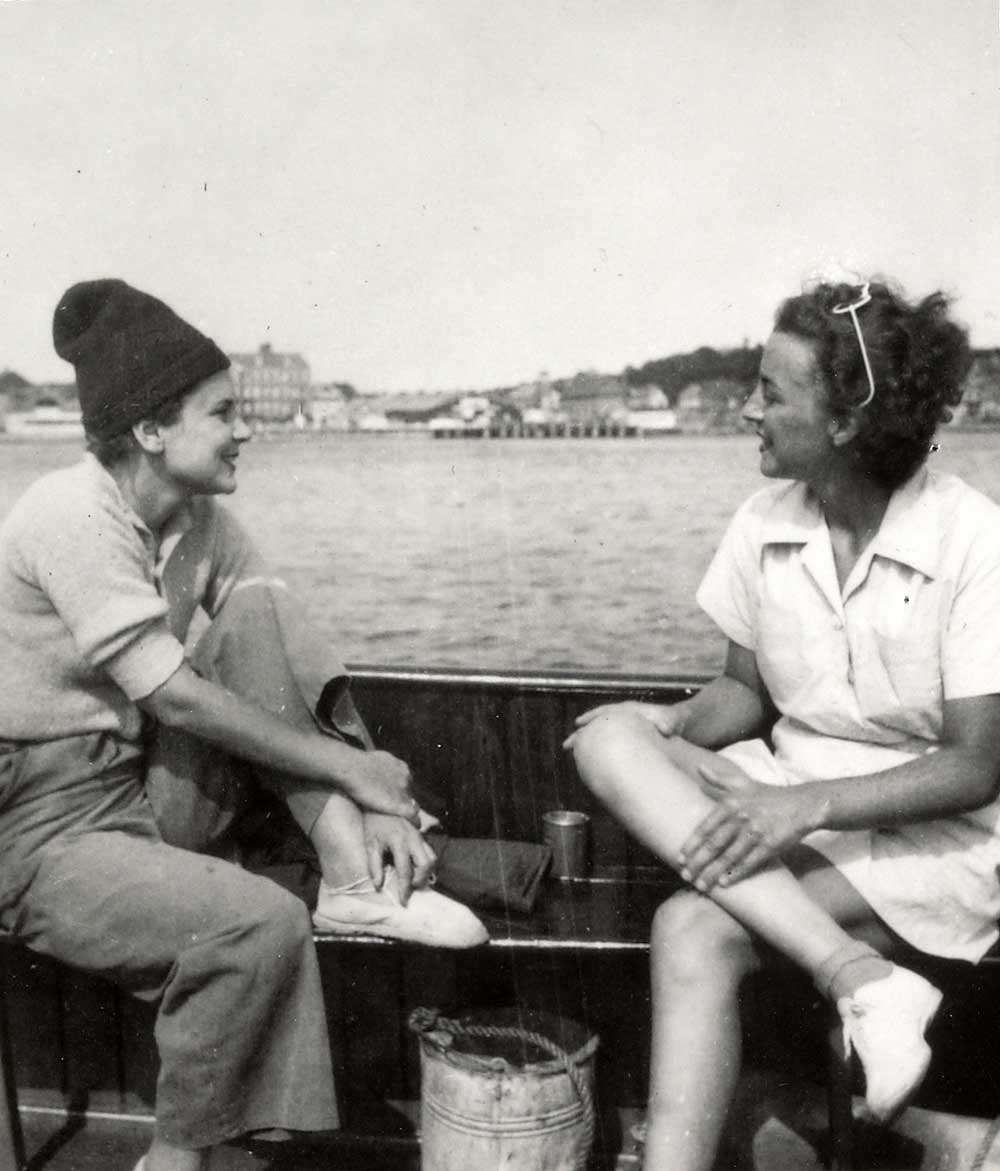

Patricia: Before seeing your film, I had no idea Bishop even took photographs.

Barbara: I was completely taken by surprise! I saw these small snapshots of the nuns on the beach in her archive. They were the on 3 x 5” paper with scalloped edges like my parents snapshots when I was a child. I said “OMG, these are great!” The scale, the compositions, the exposure. There are 5 or 6 of them, and I just had to re-photograph them for the film. Then I began noticing in my collection of Bishop images that she often had a camera around her neck or in her hands. She was multi-talented. She also studied music in college as well as literature.

Patricia: The whole film is just beguiling to the eye, the sequences of the water dripping with the palm tree swaying in the breeze, all the electrical wires. I found this sequence very complimentary to the rhythms of Bishop’s own construction of erotic charges—such as “Close as two pages in the book who read each other… head to toe.” In both instances, the structure is filled with anticipation.

Barbara: That is my favorite little visual poem in the film as well! I was on a residency in Key West for the month of January, 2014 and i was able to experience downpours, deluges, sparkles of electric energy in the air while living in my tiny wooden house a block away from Bishop’s.

There is a charge, a sensual charge to the semi-tropical warmth, the wide leaved flora spread out to capture liquidity, the thunderous claps then sharp cracks of lightening. Weather is erotic. We are made up mostly of brain connections to skin surface through the little cilia (hairs) that allow us not only to locate where we are in space but, also I think, alert us to our own erotic time.

Patricia: Quite early on in the video, we hear these lines from Bishop: “You are an I, you are an Elizabeth, you are one of them /I scarcely dared to look to see what I was…” These lines are so packed with the power of self-looking, and looking from the self.

Barbara: These lines are some of the most profound that Bishop ever wrote. If we can believe them, and, I do, they show that as a very young girl she had an awakening of subjective agency. She saw/felt/thought herself as separate and unique and yet connected to a heritage. She was in Worcester with her paternal grandparents, a place she didn’t like quite stuffy and rule-bound compared to the Great Village working class home she preferred, and I suppose that Aunt Consuelo represented a part of the family with which she hadn’t identified with as yet. This ‘shock of being’, of consciousness, was a merger not only with one half the family, but also with all of humanity including those pictured in the National Geographic (images of foreign, naked women whose breasts horrified her). Seven years old! Able to read! Genius Bishop, I say!

Welcome To This House premiered at The Museum of Fine Art, Boston and The Museum of Modern Art, New York in 2015. For forthcoming screenings visit the director’s website: www.barbarahammer.com.